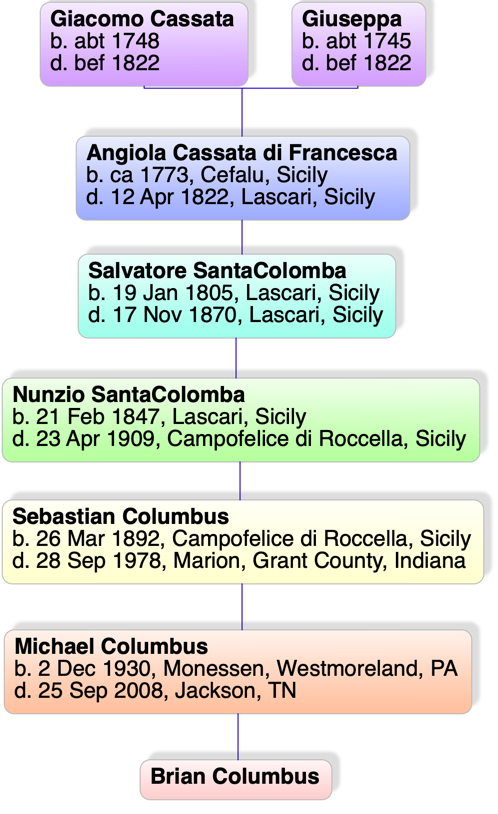

Sometimes I pick an ancestor that’s sitting at the end of a line, and focus on him or her, trying to find another record of their life. After all, I know whoever it is, there was a birth, a death, and a mother and father.

Recently I picked Angiola Cassata, my GGG-Grandmother, born in the late 1700s who died in 1828, in Lascari, Sicily. I didn’t have anything that told me her parents’ names, and wanted to know where she came from. I had already looked through the Antenati collection for the actual death record, but surprisingly came up empty. I had an extraction of it from her son’s marriage record in 1836, so I went back to look more closely at that, and realized it was 1822, not 1828. (Sometimes the handwriting is very hard to read.)

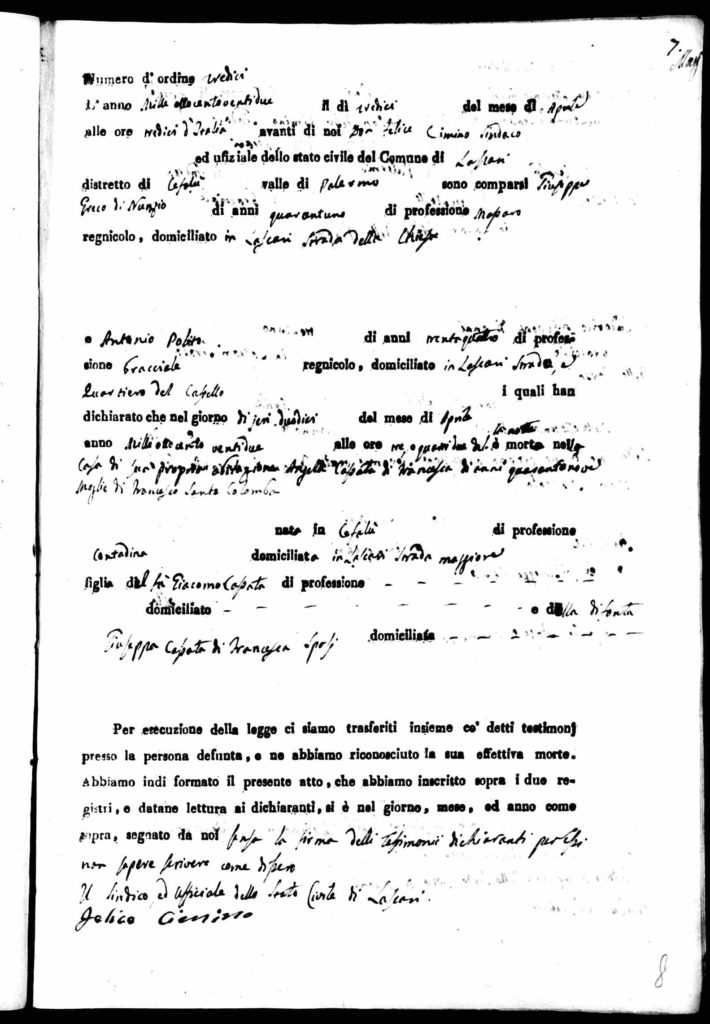

Back in Antenati, I found it:

Death records, particularly during this period in Sicily, were very standardized, following a kind of template where the blanks are filled in by the official from the commune. The deceased’s name, spouse, parents, occupation, age and place of birth were all included, so it can be a real gold mine. The cause of death – which would be an interesting element – is never included. This same layout of information, beginning with the witnesses (almost always two, and usually not the spouse or parent of the deceased) was used at least as far back as the mid-1700s, when the records were in Latin, rather than Italian, and all hand-written, as opposed to one like pictured here.

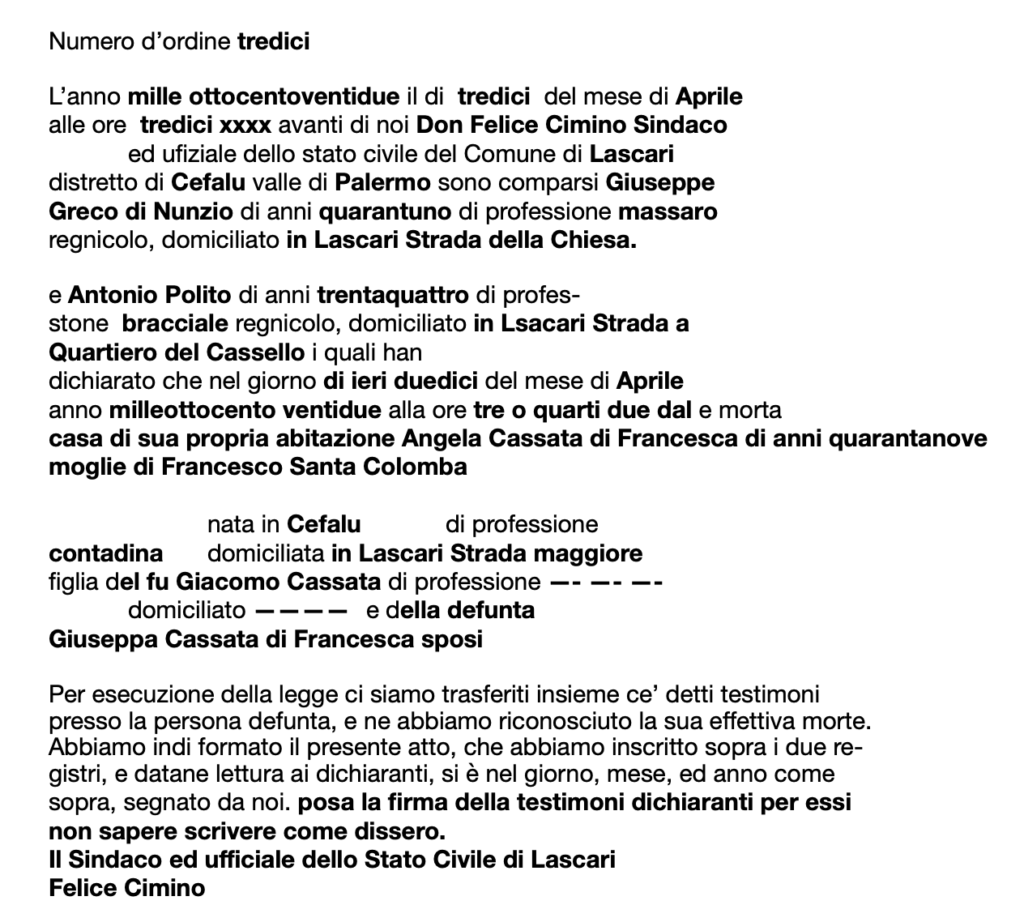

Below is a transcription of the Italian, as best as I could do, probably full of errors. This person’s handwriting wasn’t the easiest to read. The handwritten parts are in bold:

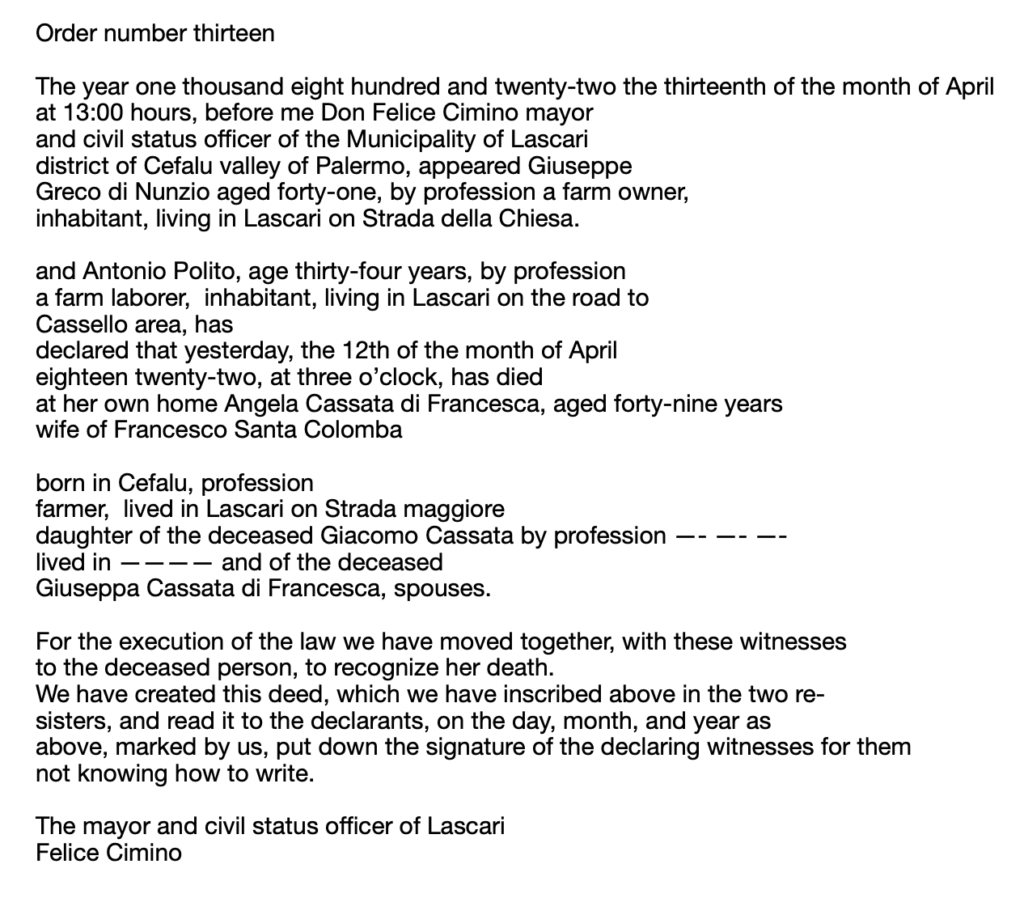

And a basic translation to English:

The “del fu” and “della defunta” indicate her parent’s are deceased, so I can’t learn occupations or residency. I would guess they live in Cefalu, as that was Angela’s birthplace, and like most of the family they were likely farm workers, aka contadina.

There are a few interesting things about this document. Often the witnesses, who are typically men, will be listed as “figlio di….”, to identify exactly who it is. In fact, in many records, identifying a person’s parents (or at least father) is documenting the identity of the person in question. This is a helpful technique in a culture with strong naming traditions that result in first cousins often having the same names. Children have the same surname as their father, but women didn’t take on a husband’s surname when marrying.

So what’s interesting here:

The first witness is identified as “Giuseppe Greco di Nunzio” and the second witness isn’t noted as the son of anyone. Was Giuseppe’s surname Greco and his father Nunzio, and it should’ve been written Giuseppe Greco figlio di Nunzio”? I would think so.

Angela’s name is listed as “Angela Cassata di Francesca“, her father is listed as “Giacomo Cassata” and her mother as “Giuseppa Cassata di Francesca“.

As I noted, women didn’t take their husband’s surname, and when I first found Angela’s name it was on her son Salvatore’s death record, many years later, in 1870, and she was listed as Angela Cassata. But I’ve now seen (at least from this commune, Lascari) that sometimes (?) a woman’s name is written with her husband’s surname. When I found Angela on her son’s marriage record, which included her death record extract, she was Angela Santacolomba on al all those pages. And here again, her mother is being listed with her husband’s surname .

Or is it? Why are the mother and daughter listed with the “di Francesca” part but Giacomo isn’t? Is the surname Cassata or Cassata di Francesco?

Was the witness Giuseppe Greco, or Giuseppe Greco di Nunzio?

Clearly I need to learn more.

or Cassata di Francesca