I’ve been at this research for over 20 years now, and I think I’ve officially broken the barrier of the 1600s!

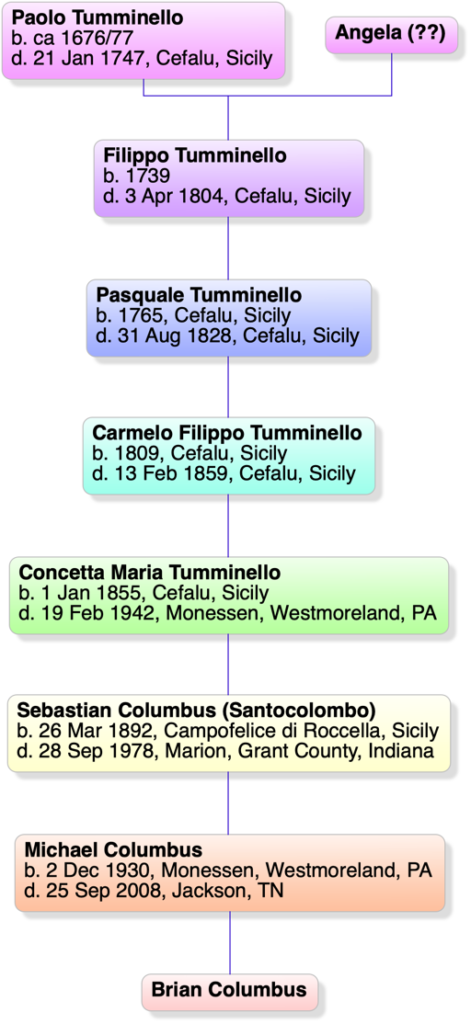

Thanks to the diligent, hard work of other researchers who thankfully document their sources, I was led this week to this document:

In June 1824 my great-great-great-great-great-uncle, Antonino Tumminello, was getting married. He was a 63 year-old widower, with several grown children, working as a “contadino” and was engaged to a 42 year-old widow. Part of getting married required providing proper approval from parents, along with documentation of one’s birth records. When parents are deceased, a village official will provide proof that the death was recorded.

Not surprisingly, Antonino’s father was deceased, and therefore a record was made of his death.

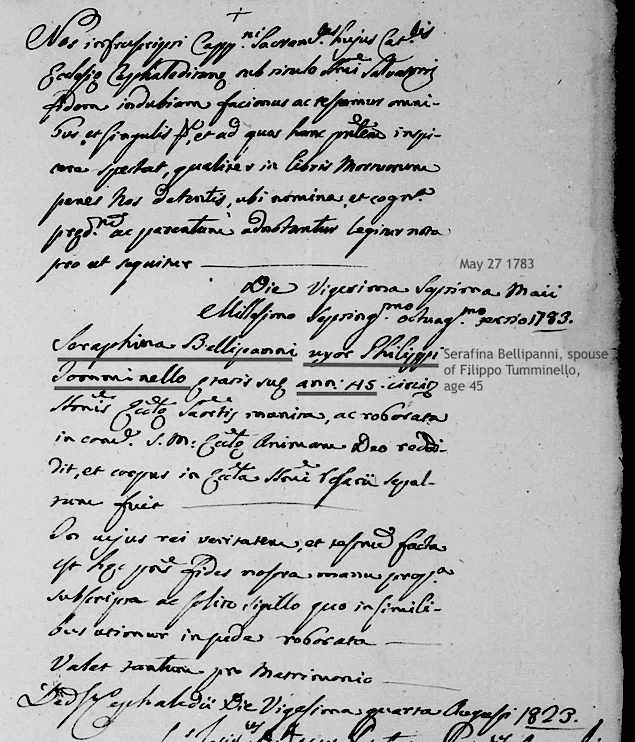

And his mother was also deceased, many years prior.

I already knew Uncle Antonino’s parent’s names – it’s really the only way I knew he was my uncle, but I didn’t have their death information. Often a death record will list the decedent’s parents, but sometimes, as is the case here, the spouse is referenced.

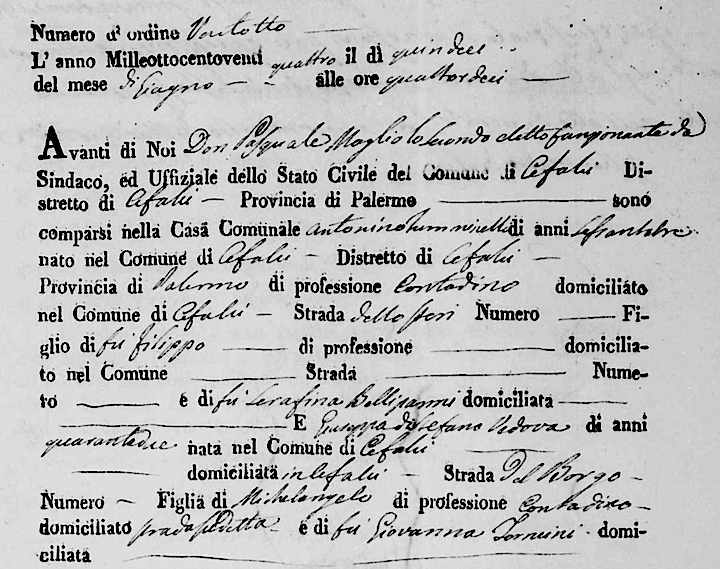

But, importantly, if parents are not alive to provide permission for the person to marry (even if it’s their second marriage) then the responsibility will go back to the grandparents, and therefore this gem was also in the pile:

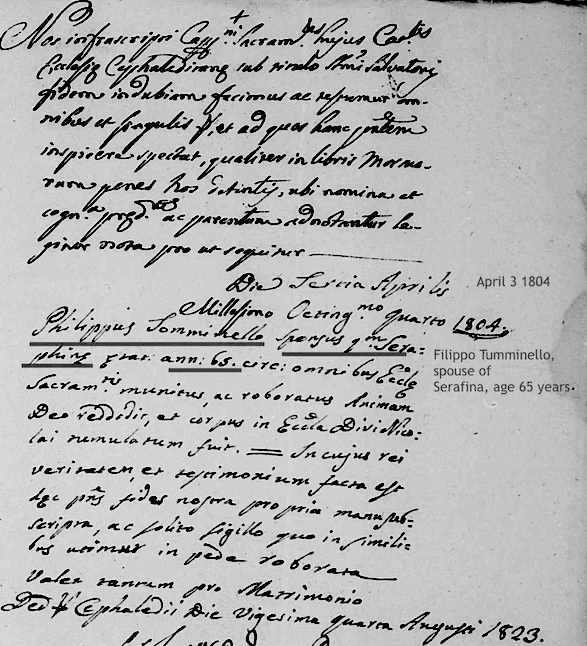

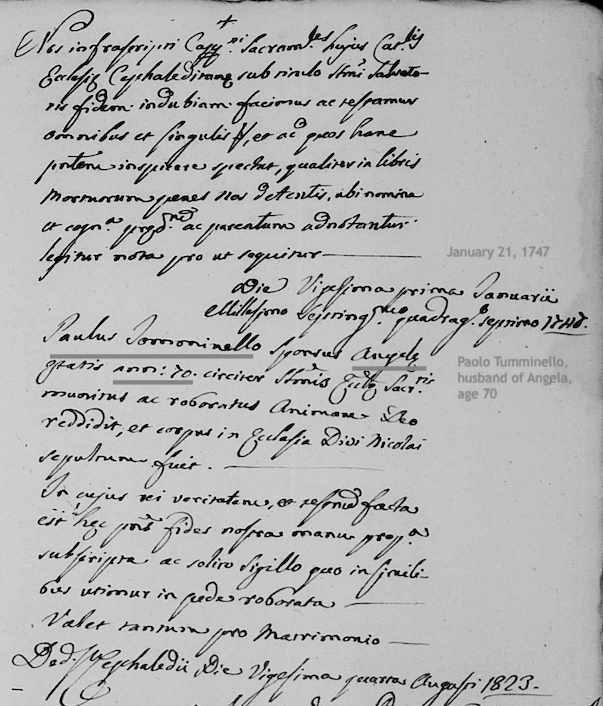

Antonino’s paternal grandfather’s death also needed to be noted, and so it too was documented. He died in January 1747 at age 70, which means he was born in 1676 or 1677! While I’ve information on several people who lived in the early 1700s, I haven’t had anything concrete like this to really break that barrier.

There are a few interesting facts and a few questions these documents reveal:

- My 5G-Grandfather was Paolo Tumminello (1676/77 – 1747)

- My 5G-Grandmother may have been named Angela, but that’s actually unconfirmed.

- Paolo became a father to Filippo, it seems, at around age 62. (!?!) That’s kind of late. It makes me wonder if the original record that the village officials looked at was hard to read. Could he have died at age 60 instead, making him a father at 52 – a more likely age? Assuming the age on the original death record was written out (and I can’t be sure) the word sixty in Latin is sexaginta, while seventy is septuaginta. Even with difficult to read writing, those two seem unlikely to be mistaken for each other. How I find that record – even if I could find that record – I’m not sure.

- Why were these records, which are noted as being documented for the purposes of a marriage, dated August 1823, when Antonino didn’t remarry until June 1824? His first wife, Rosaria Culotta, died in June 1823 – so two months later he obtains the documents to remarry, but doesn’t do that for almost a whole year? I might have to piece more together around this, if I can.

Each new discovery seems to bring on a new set of questions and wonder, but my fascination and enjoyment of the hunt never waivers, and this new information on my Tumminello ancestors is certainly no exception.